A wall that still divides

David Ahern

Current editor of The Majellan, David has spent more than 40 years as an editor/journalist

There’s been a lot of talk in recent years about building walls. While some people, sadly, believe such barriers should be used to deter refugees and asylum seekers, walls have also been erected in the past to keep opposing factions apart.

There’s been a lot of talk in recent years about building walls. While some people, sadly, believe such barriers should be used to deter refugees and asylum seekers, walls have also been erected in the past to keep opposing factions apart.

Take Belfast, for example. The issue of walls took on greater personal significance when I recently visited the city. The sectarian troubles that had racked Belfast, particularly in the 1970s and 80s, seemed confined to the history books, overtaken in the modern era by the violence and cruelty of Islamic terrorists and white supremacists.

However, I was surprised to discover many of the long-standing enmities are simmering just under the surface, not helped by the difficulties around Brexit. I wrongly believed the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 had largely resolved the problems between Catholics and Protestants.

The peace accord has certainly stopped the bombings and tit for tat shootings that had claimed countless lives over the preceding decades but underlying resentment and animosity, for some, still remain. It is a lingering bitterness that we in Australia don’t truly understand, as any tension and anger here between the various Christian faiths ceased many decades ago.

While the Berlin Wall came down in the 1980s, this wall – notably between the Shankill and Falls roads in West Belfast – is a forceful reminder of the divisions that still exist between the Protestant and Catholic communities.

I visited Clonard, the Redemptorist monastery (Church of the Most Holy Redeemer) and learnt that the wall runs along the perimeter of the church on the other side of the road. Protestant families live within a stone’s throw from the monastery behind an eight-metre high wall.

It’s one thing to recall the television news reports about the hostilities from the past but gazing out of the monastery windows at the ugly reminder of sectarian animus is another thing altogether. It’s quite surreal.

The hatred between Catholics and Protestants runs deep and was not new to the late 20th century. Indiscriminate killings on both sides of the religious divide, for example, occurred in Belfast in the early 1920s.

One of those to lose their lives during the city’s troubled past was Redemptorist Brother Michael Morgan. Father Brendan McConvery, an Irish Redemptorist, gave me a guided tour of Clonard and showed me the spot inside the monastery where Br Morgan was shot and killed by a British soldier in 1920.

It was a part of Irish history unknown to me and while his death was almost 100 years ago, I was still saddened to hear about it. While I was in Belfast, I also learnt a lot about Father Gerry Reynolds, a Redemptorist priest, who devoted much of his latter life encouraging peace between Catholics and Protestants.

Fr Gerry had suggested to Rev Burch they meet the family of Denis Taggart, a part-time sergeant with the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), who was shot and killed outside his home by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). His son, aged 13 at the time, came home soon afterwards to find his father.

Rev Burch said later that Denis’ mother and Fr Gerry cried when he presented her with a carving of a weeping Jesus. Dr Gladys Ganiel, who wrote a biography on Fr Gerry (Unity Pilgrim The Life of Fr Gerry Reynolds CSsR), said the grieving mother told Fr Gerry if the gunmen had known her son “they never would have killed him.” This comment strongly resonated with Fr Gerry.

Fr Gerry was also great friends with the Rev Ken Newell, a Presbyterian Minister. Despite criticism from politicians and religious on both sides, their friendship over time resulted in increased dialogue between the warring paramilitaries.

“Thankfully there are now dozens of Christian groups beavering away together to defrost the lingering suspicion-laden religious attitudes and in their place generate the warmth of spiritual openness, hope and peace,” wrote the Rev Newell in the Irish Redemptorist newsletter, Reds.

“It is an indubitable fact that no Catholic priest in the history of Ireland has attended and befriended more Protestant churches than Fr Gerry Reynolds. Our friendship focussed on ending violence, eroding the spiritual apartheid between the churches, and nurturing a process of dialogue which would lead towards exclusively democratic and inclusive(ness) which would stimulate greater communal reconciliation.”

Fr Brendan, also writing in Reds, said Fr Gerry was committed to Christian unity.

“For Gerry Reynolds, the journey towards unity of all the Christian churches was nothing less than the moment when they would share the Body of the Lord at the common table,” says Fr Brendan. “During the last years of his life, each Sunday morning, he led a group of ‘Unity Pilgrims’ to a service in a Protestant Church somewhere in Belfast.

“For him, it was important to observe the discipline of his own church and of the host church.”

Fr Gerry also had a strong connection to Charles de Foucauld’s spiritual teachings (see story on page …). “Gerry Reynolds was a natural contemplative. It is probably one of the reasons he was so drawn to the spirituality of Charles de Foucauld, through both the priestly fraternity and his friendship with the Little Sisters of Jesus,” says Fr Brendan.

“Contact with de Foucauld’s spirituality paradoxically led him back to aspects of his own Redemptorist tradition, with its emphasis on the mystery of Christ as ‘Crib, Cross and Sacrament, in which daily adoration was normal and its preference to preach the Gospel to the poor.”

One of the great things about travelling is the educational aspect, taking in new sights and learning about the local people. Even though I work for a Redemptorist publishing house, Majellan, the Gerry Reynolds story was on the whole a mystery to me. Visiting Belfast and Clonard gave me insights into the man who, in his own way, contributed so much to a more ‘peaceful’ Northern Ireland.

With the muddle that is Brexit still working its way toward a resolution of sorts, one can only hope and pray the work of Fr Gerry, and the many others, doesn’t unravel in the years ahead. Fr Gerry Reynolds, the Redemptorist priest and peacemaker, died aged 80 on November 30, 2015. What a remarkable and true man of Christ he was.

Image: Clonard Church in Belfast and the barrier separating Catholics and Protestants.

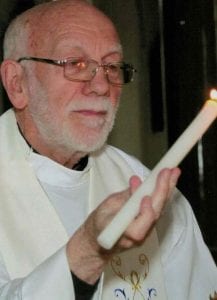

Image: Father Gerry Reynolds. Photo appeared in the book Unity Pilgrim by Gladys Ganiel (Redemptorist Communications).